Per decenni, a partire dagli anni ’30, le minoranze etniche presenti negli Stati Uniti hanno subito il fenomeno del redling.

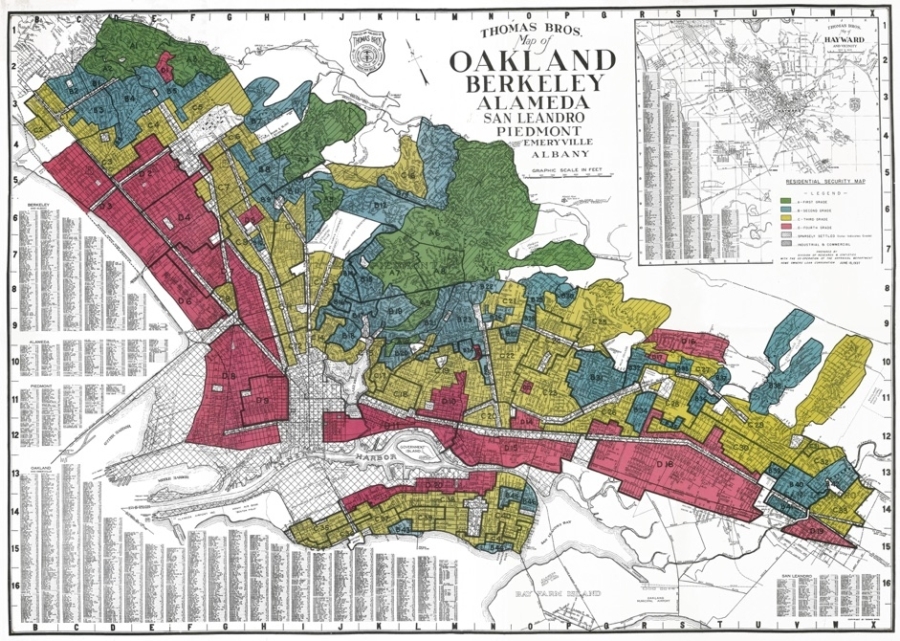

Il termine deriva dall’uso, per la prima volta da parte dell’agenzia federale dell’ Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (corporazione nata nel 1933 che si occupava di ipoteche) ma poi anche di altre banche e creditori, di contrassegnare in rosso nelle mappe della città i quartieri in cui vivevano per la maggioranza afro e latino americani. Questi venivano considerati come a maggior rischio di non riuscire a pagare un debito, e le banche negavano prestiti e ipoteche ai residenti di questi quartieri.

Oggi questa pratica non è più legale grazie a due leggi:

-il Fair Housing Act del 1968, che vieta la discriminazione razziale di chiunque voglia compiere azioni sulla propria casa, e l’imposizione di interessi eccessivi;

-il Community Reinvestment Act del 1977, secondo cui coloro che fanno credito devono tracciare quanto spesso approvano e negano prestiti a famiglie con un basso reddito.

Ma, nonostante queste leggi, il fenomeno del redlining lascia le sue tracce ancora oggi: la Hudson City Saving Bank (una delle banche più importanti per quanto riguarda il mercato delle case americano), per esempio, ha dovuto pagare un risarcimento di quasi 33 milioni di dollari dopo che, in seguito ad un’investigazione, si è scoperto che tra il 2009 e il 2013 ha evitato di concedere ipoteche a afroamericani e latinoamericani. Anche la Evans Bank ha dovuto pagare 825.000 dollari dopo che si scoprì che nelle mappe usate per determinare i prestiti la banca cancellava i quartieri di maggioranza straniera. Inoltre il procuratore generale di New York, Eric Schneiderman, sostiene che delle 1100 ipoteche che la banca ha concesso tra il 2009 e il 2012, solo 4 erano per famiglie afroamericane.

E questi sono solo alcuni dei casi di redlining che si verificano ancora oggi.

Il fenomeno che si presenta di più sembra essere il cosiddetto reverse redlinig, ovvero l’applicazione di ingenti interessi ai prestiti destinati a persone che abitano i quartieri un tempo contrassegnati dal redlinig. Per esempio, nel 2014 Los Angeles ha fatto causa a ben 4 banche (J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo e Citigroup) che non solo applicavano la redlining tradizionale ma anche quella inversa applicando interessi spropositati alle comunità di colore, dal 2004. E questi sono solo alcuni esempi.

Dunque, nonostante le mappe contrassegnate siano ora illegali, il problema del redlining non è scomparso. O perlomeno non è scomparsa la sua discriminatoria idea di fondo per cui la maggioranza etnica di un paese tende a considerare le persone facenti parte di minoranze come meno affidabili. E certamente questa idea non è esclusivamente americana.

Di Camilla Gorgati

Traduzione di Camilla Gorgati

REDLINING: HAS THIS RACIST PRACTICE REALLY DISAPPEARED?

For decades, starting in the 1930s, ethnical minorities in the USA endured the redlining phenomenon.

The term derives from the habit, started by the federal agency Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (corporation that takes out mortgages since 1933) then followed by others banks and creditors, of marking with red ink black and latino neighborhoods in the city maps. These were considered as riskier of default, and banks denied loans and mortgages to people who lived in these areas.

Today, this activity is no longer legal because of two laws:

-the Fair Housing Act of 1968, that bans discrimination based on anyone’s race when the person is trying to do any sort of action on a home, and it bans excessive interest rates as well.

-the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, that obliges lenders to track how often they approve and deny loans to people in low-income households.

However, despite these acts, the effects of the redlining phenomenon are still present today: the Hudson City Saving Bank (one of the most important banks in the American house market), for example, had to pay almost 33 millions dollars when, after an investigation, it had been discovered that between 2009 and 2013 the bank refused to took out any mortgage on African Americans and Latin Americans. Also Evans Bank had to pay 825.000 dollars after it came out that in the maps that were used to track loans the bank erased the areas with a majority of foreign people. Also, New York’s attorney general Eric Scheniderman sustains that only 4 of the 1100 mortgages that the bank took out between 2009 and 2012 were for people of color’s households.

And these were only few cases of redlining that are still happening today.

The most frequent phenomenon seems to be the so-called reverse redlining, which means engaging predatory loans in the same areas that were once redlined in maps. For example, in 2014 Los Angeles prosecuted 4 banks (J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo e Citigroup) for applying both traditional and reverse redlining, imposing high interests to the black community, since 2004. And these are just a few examples.

So, although the marked maps are now illegal, the problem of redlining has not disappeared. Or at least what has not disappeared is the discriminatory idea that the ethnical majorities tend to consider the minorities as less reliable. And this idea is for sure not just American.